Blog

Beyond the uncanny valley of 3D bones

October 27, 2022

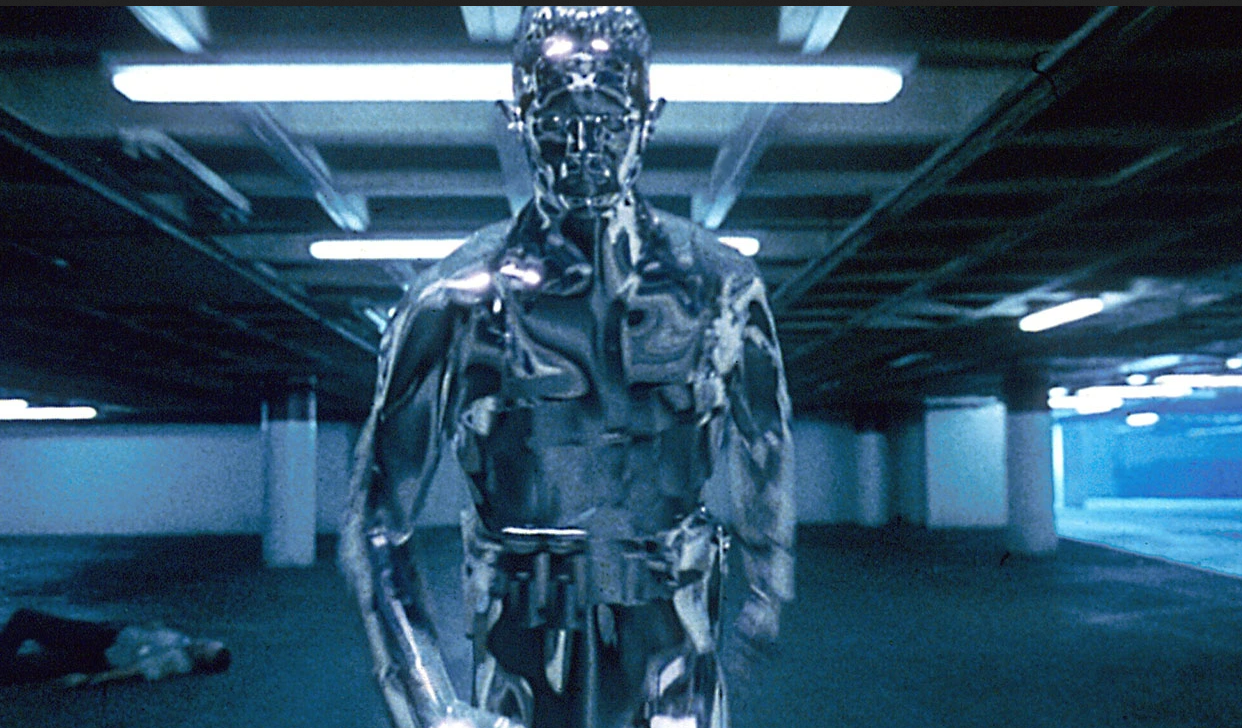

3D animation reached new heights in Hollywood with movies likes The Abyss (1989) and Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991). The acclaimed liquid tentacles in The Abyss and the liquid metal terminator in Terminator 2 were both made using an animation technique known as metaballs.

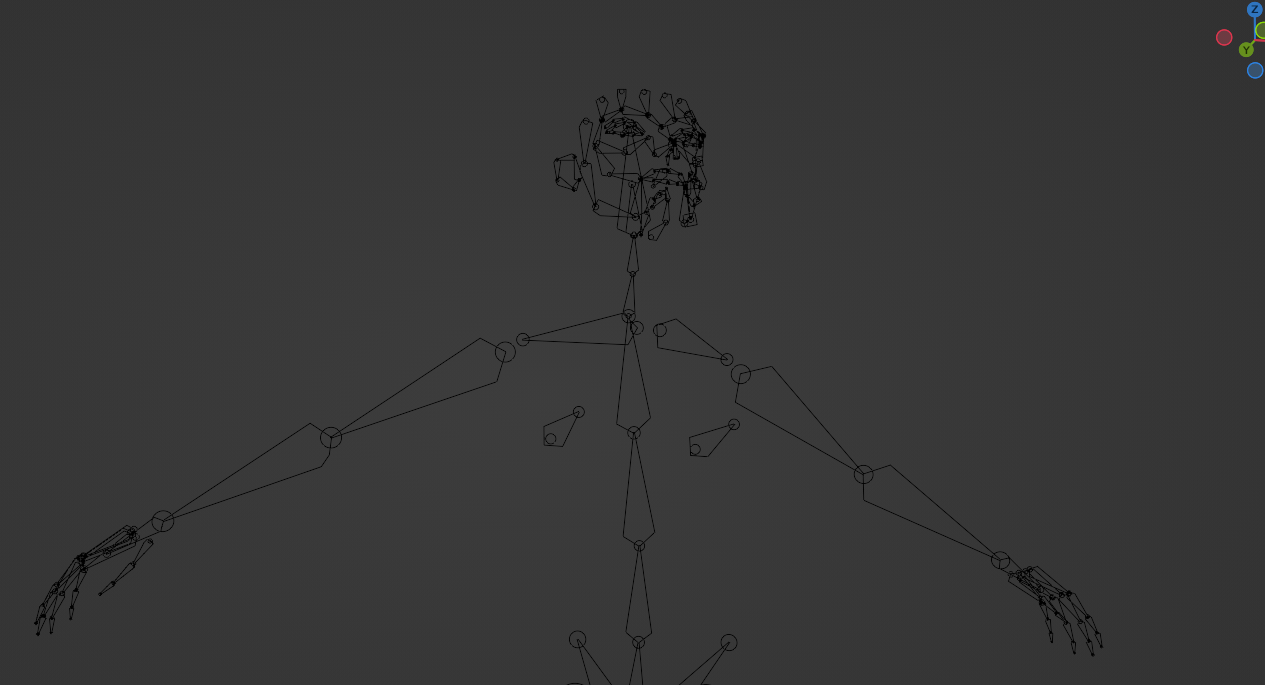

In the 1990s, the metaball 3D technique was quickly replaced in the industry by 3D bones on static meshes, which still remains a mainstream fallback some consider cutting edge.

Bones: Not as dynamic as they’re cracked up to be

When the shift to bones took place in 3D industries, the expressive possibilities available to animators was limited.

On the one hand, the metaball technique uses dynamically tessellated geometry, where the number of vertices are recalculated each frame to simulate liquid surface.

On the other hand, bones only move the points that are there (deform), rather than create points, limiting how dynamic the animation can be. With bones, the topology is static – the number of points is fixed, the tessellation is fixed.

Bones also create problems for rendering. Bone and bone calculations on the GPU are slow and not a friendly thing to mix with instance rendering. When bones are used, game engines cannot render very many characters at once, slowing production pipelines.

Creating high-quality 2D/3D animation using Grease Pencil

Smooth, fluid animation is not defined simply by a higher frame rate. For example, Dragon Ball Z (1989-1996) was 12 frames per second, yet widespread audiences recognized and appreciated its fluidity.

Low frame rate animation with well-chosen key poses can have more impact combined with data compression techniques and specialized shaders. Our brains can very quickly fill the in-between frames with something that can be even better.

Animation specialized to take advantage of low frame rate can help us overcome the uncanny valley problem -- when things are meant to look realistic, yet lack some missing ingredient to fulfill that aim.

When everyone else is stuck with bones on static meshes, creative solutions beyond bones are necessary to take the cutting edge further.